Social scientists investigating discourse and framing

Complete beginners with basic R knowledge

Anyone curious about how language actually works in practice

Tutorial Citation

If you use this tutorial, please cite as:

Schweinberger, Martin. 2026. Finding Words in Text: Concordancing. Brisbane: The Language Technology and Data Analysis Laboratory (LADAL). url: https://ladal.edu.au/tutorials/kwics/kwics.html (version 2026.02.08)

Have you ever wondered how researchers find patterns in massive collections of text—whether in tweets, novels, news articles, or historical documents? One of the most powerful techniques is concordancing: the systematic extraction and display of words or phrases along with their surrounding context.

The KWIC Display: Your Window into Language Use

When you perform a concordance search, the results typically appear in a keyword-in-context (KWIC) display. Imagine looking through a window where your search term—the node word or search term—appears highlighted in the center of each line, with words before and after it neatly aligned:

...couldn't help thinking there must be more to life than being

...you are my density. I must go. Please excuse me. I mean

...situation requires that we must work together to achieve our

...extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence before they

...but the Emperor has no clothes! We must speak truth to power and

This simple but powerful display format reveals patterns invisible to casual reading. By presenting multiple instances simultaneously, concordances let you see:

How words are actually used (not how we think they’re used)

What words consistently appear nearby (collocation patterns)

Different meanings and senses of the same word

Grammatical patterns and constructions

Register and genre variations

Beyond Individual Words: The Power of Context

Traditional reading presents texts linearly—one sentence after another, one page after the next. Concordancing transforms this experience by making texts queryable, turning them from objects to be read into databases to be investigated. This shift in perspective has revolutionized language research.

Consider the word “run.” You might have strong intuitions about how it’s used. But a concordance instantly reveals whether an author primarily uses it:

- As a verb (“run fast”)

- As a noun (“a long run”)

- In phrasal verbs (“run into”, “run out”)

- In idioms (“run for office”, “run the show”)

And crucially, concordances show you the company a word keeps—its collocates—revealing associations that might never emerge from reading alone.

Why Concordancing Matters

Concordancing isn’t just a technical procedure—it’s a fundamental methodology that addresses core challenges in language research.

Bridging Intuition and Reality

Native speakers have strong beliefs about their language. We feel confident about word meanings, frequency, and usage. But these intuitions can be surprisingly inaccurate when confronted with corpus evidence.

Example paradoxes:

- We think we use “very” more than “really” (corpus evidence often shows the reverse)

- We believe formal writing avoids contractions (many genres use them strategically)

- We assume certain collocations are rare (they might be pervasive in specific registers)

Concordancing grounds claims in observable, verifiable data rather than introspection alone. This empirical foundation makes linguistic analysis more rigorous and falsifiable.

From Observation to Discovery

Concordances enable several crucial research operations:

1. Semantic Analysis

- Identify different senses of polysemous words

- Observe how context disambiguates meaning

- Track semantic prosody (positive/negative associations)

- Map conceptual metaphors and framing

2. Collocational Analysis

- Discover words that habitually co-occur

- Identify significant vs. accidental co-occurrences

- Build collocational profiles of terms

- Compare usage across varieties or time periods

3. Grammatical Investigation

- Examine verb complementation patterns

- Study preposition selection

- Analyze word order variations

- Investigate grammaticalization processes

4. Discourse Analysis

- Track how concepts are discussed

- Identify discursive strategies

- Examine attitude and evaluation

- Study ideology and framing

5. Historical Linguistics

- Compare usage across time periods

- Document language change

- Trace the development of constructions

- Study obsolescence and innovation

The Quantitative-Qualitative Bridge

Concordancing uniquely bridges quantitative and qualitative analysis:

Quantitative aspects:

- Frequency counts (how often does it occur?)

- Distribution patterns (where does it occur?)

- Collocational strength (what co-occurs significantly?)

- Statistical significance (are patterns real or random?)

Qualitative aspects:

- Close reading of individual instances

- Interpretation of nuanced meanings

- Recognition of contextual factors

- Understanding of pragmatic effects

This combination makes concordancing invaluable for mixed-methods research that requires both breadth and depth.

The Cognitive Science of Concordancing

Understanding why concordances work so well requires appreciating how humans process language.

Pattern Recognition and the Human Brain

Humans excel at recognizing patterns, but we have limitations:

Working memory constraints:

- We can hold only 4-7 items in working memory simultaneously

- Traditional reading makes it hard to compare distant instances

- We forget earlier examples while reading later ones

Concordances overcome these limits by:

- Displaying multiple instances simultaneously

- Aligning examples for easy comparison

- Externalizing the comparison task

- Supporting visual pattern recognition

Confirmation bias:

- We tend to notice examples confirming our beliefs

- We overlook counter-examples

- We remember exceptional cases more than typical ones

Concordances combat bias by:

- Presenting all instances (not just memorable ones)

- Showing frequency and distribution objectively

- Making absence as visible as presence

- Supporting systematic rather than selective analysis

From Reading to Querying

Concordancing fundamentally changes how we engage with texts:

Traditional Reading:

- Linear, sequential processing

- Author-determined order

- Focus on content and narrative

- Individual texts as complete units

Concordance Analysis:

- Non-linear, query-driven investigation

- Researcher-determined retrieval

- Focus on linguistic patterns

- Texts as data repositories

This shift parallels the transition from libraries (browse and read) to databases (query and retrieve). Both modes are valuable, but concordancing opens analytical possibilities unavailable through reading alone.

Applications Across Disciplines

Concordancing serves diverse scholarly and practical purposes across multiple fields.

Linguistic Research

Corpus Linguistics:

- Document authentic language use at scale

- Test theoretical claims against evidence

- Discover patterns invisible to introspection

- Build usage-based grammatical descriptions

Example: Investigating Verb Complementation

A researcher might use concordances to examine whether “enable” prefers infinitival complements (“enable us to succeed”) or nominal complements (“enable success”), and whether this varies by register.

Sociolinguistics:

- Compare language use across social groups

- Track variation by age, gender, region, etc.

- Document style-shifting and register variation

- Study language and identity

Example: Gender Differences in Modal Usage

Concordances can reveal whether men and women use epistemic modals (“might”, “could”, “perhaps”) at different rates in professional emails, testing claims about gendered communication styles.

Historical Linguistics:

- Track language change over time

- Document semantic shifts

- Study grammaticalization

- Identify obsolescence and innovation

Example: Tracking Grammaticalization

Concordances can show how “going to” evolved from a verb of motion to a future marker by examining its contexts across centuries.

Language Teaching and Learning

Data-Driven Learning (DDL):

Rather than memorizing rules from textbooks, students discover patterns through guided concordance analysis.

Vocabulary Instruction:

- Show authentic usage examples

- Illustrate collocational patterns

- Demonstrate register appropriateness

- Build intuitions about natural use

Example: Teaching Phrasal Verbs

Instead of lists, students examine concordances of “put off”, “put up with”, and “put down” to discover meanings from context and observe typical subjects, objects, and situations.

Grammar Instruction:

- Illustrate grammatical constructions in authentic contexts

- Show frequency and typicality

- Demonstrate exceptions and edge cases

- Build corpus-informed materials

Writing Instruction:

- Show students how professional writers use language

- Demonstrate discipline-specific conventions

- Illustrate effective rhetorical strategies

- Provide authentic models

Example: Determining Authorship

Concordances of function words, punctuation patterns, and favorite expressions can distinguish authors even when content differs.

Stylistic Analysis:

- Track recurring motifs and themes

- Analyze characterization through dialogue

- Study narrative technique and voice

- Examine evolution across an author’s career

Example: Color Imagery in Poetry

Concordances of color terms reveal an author’s symbolic system, showing whether colors carry consistent associations or shift across works.

Comparative Literature:

- Compare authors, genres, or periods

- Identify influence and intertextuality

- Study translation strategies

- Examine cultural framing

Translation Studies

Parallel Concordancing:

Aligning source and target texts allows translators to:

- Find equivalents for difficult terms

- Identify translation strategies

- Maintain consistency across large projects

- Build translation memories

Example: Technical Translation

A translator working on a manual can concordance source and target texts to see how other translators rendered “interface” in different contexts, ensuring consistency.

Translation Quality Assessment:

- Identify under/over-translation

- Detect shifts in register or style

- Spot consistency issues

- Evaluate naturalness

Lexicography

Modern dictionaries increasingly rely on corpus evidence obtained through concordancing rather than lexicographer intuition alone.

Dictionary Compilation:

- Identify all senses of polysemous words

- Find authentic example sentences

- Document collocations and phraseology

- Determine frequency and currency

- Discover new words and meanings

Example: Defining “Cloud”

Concordances reveal technical senses (“cloud computing”, “cloud storage”) that didn’t exist when older dictionaries were compiled.

Content Analysis and Digital Humanities

Discourse Analysis:

- Track how concepts are discussed in media

- Identify framing and ideology

- Study attitude and evaluation

- Document discursive strategies

Example: Climate Change Discourse

Concordances of “climate change” vs. “global warming” across news outlets can reveal ideological positioning through word choice.

Sentiment Analysis:

- Build sentiment lexicons from usage

- Identify opinion-bearing expressions

- Study emotional language

- Detect stance and perspective

Historical Text Analysis:

- Track concept evolution

- Study historical world-views

- Document intellectual history

- Examine power and ideology

Example: Democracy Over Centuries

Concordances show how “democracy” shifted from referring to ancient Athens to becoming a contested modern ideal, revealing changing political thought.

Practical Applications Beyond Academia

Search Engine Optimization (SEO):

- Identify keyword patterns

- Discover related terms

- Analyze competitor language

- Optimize content

Visualization:

- Create dispersion plots

- Display collocational networks

- Show frequency trends

- Illustrate distribution patterns

Integration:

- Combine with metadata

- Cross-reference with other analyses

- Feed into machine learning

- Support mixed-methods research

The concordance is the starting point—the analytical journey that follows determines the insights you gain.

Exercise 1.1: Critical Reading of Concordance Research

Understanding Research Applications

Find a linguistics or digital humanities paper that uses concordances (search for “KWIC”, “concordance analysis”, or “corpus study”).

Analyze:

1. What research question does concordancing address?

2. What specific patterns does the concordance reveal?

3. How does the researcher move from concordances to interpretation?

4. What would be lost without concordancing?

Reflect:

- Could this research be done through traditional reading?

- What are the advantages of the concordance approach?

- What are the limitations?

Discussion: How does concordancing change what questions we can ask about language?

Part 2: Concordancing Tools and Approaches

The Concordancing Toolkit

The landscape of concordancing tools is diverse, ranging from simple web interfaces to sophisticated programming environments. Understanding the strengths and use cases of different approaches helps you choose the right tool for your needs.

Standalone Desktop Applications

Desktop concordancing applications offer powerful functionality without programming knowledge, making them accessible to researchers across experience levels.

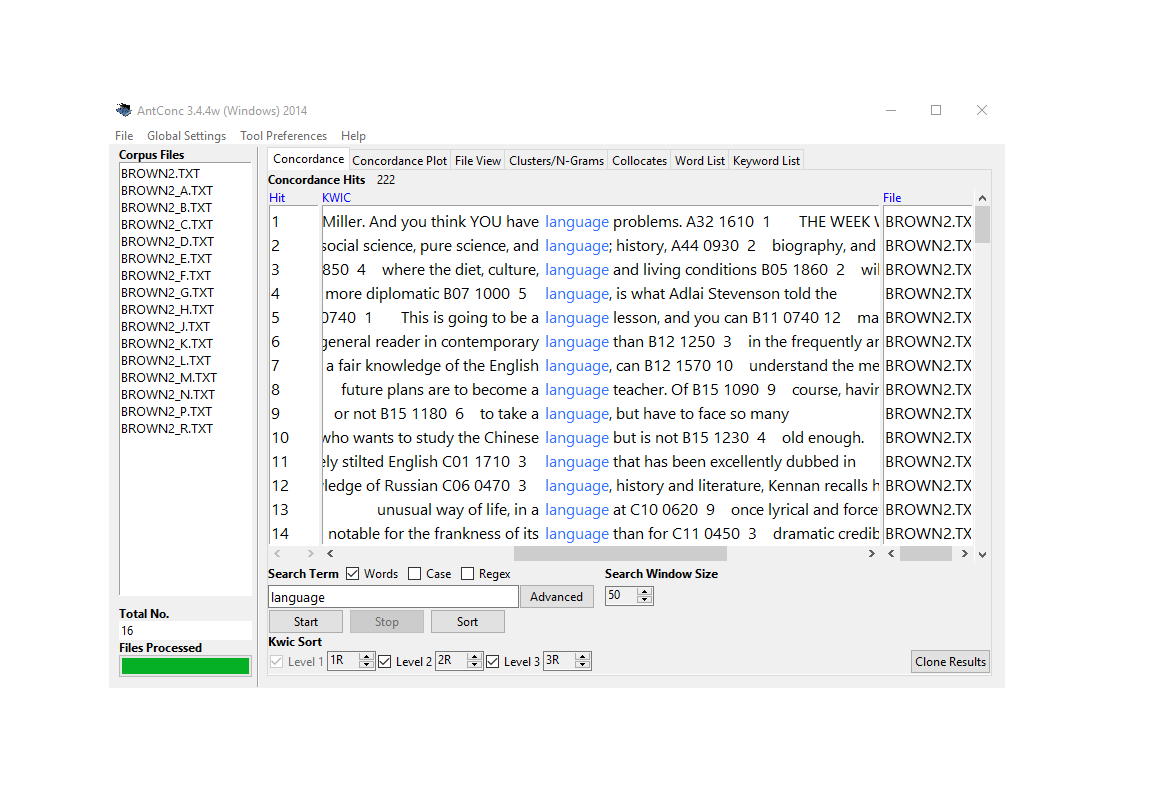

AntConc: The Standard for Teaching and Research

AntConc is the most widely used free concordancing tool, and for good reason:

Strengths:

- Completely free and cross-platform (Windows, Mac, Linux)

- No installation hassles or dependencies

- Intuitive interface ideal for beginners

- Powerful search capabilities including regex

- Beyond concordancing: collocates, clusters, keywords

- Handles large corpora efficiently

- Widely taught, extensive documentation

When to use AntConc:

- Teaching concordancing to students

- Quick exploratory analysis

- Working with local text files

- Classroom demonstrations

- Collaborative research (everyone can use the same tool)

- When you need quick results without coding

AntConc showing concordance lines for “language” with collocates panel

WordSmith Tools: The Professional Standard

WordSmith is commercial software that has long been the gold standard for corpus linguistics research.

Strengths:

- Comprehensive suite of interconnected tools

- Sophisticated statistical analysis built-in

- Dispersion plots show distribution across texts

- Keyword analysis identifies characteristic vocabulary

- Excellent documentation and tutorials

- Handles very large corpora

- Professional-quality visualizations

When to use WordSmith:

- Professional corpus linguistics research

- Publication-quality statistical analysis

- When budget allows (institutional licenses available)

- Complex multi-step workflows

- Teaching advanced corpus methods

Limitations:

- Costs money (though reasonable for professional tool)

- Windows only (though runs on Mac via Wine)

- Steeper learning curve than AntConc

- Still limited in reproducibility vs. scripting

SketchEngine: Web-Based Power

SketchEngine offers both web and desktop access with advanced features.

Strengths:

- Access to pre-loaded corpora in 90+ languages

- “Word Sketch” shows grammatical/collocational behavior at a glance

- Automatic corpus processing and annotation

- Terminology extraction for specialized fields

- Parallel corpora for translation studies

- Web interface means no installation

- Collaborative features for team projects

When to use SketchEngine:

- Multilingual research

- Need immediate access to large corpora

- Working with team members remotely

- Translation and terminology work

- When you want professional corpus preparation done for you

Limitations:

- Subscription based (though free trial available)

- Less control over corpus composition

- Learning curve for advanced features

- Depends on internet connection

Specialized Tools

ParaConc: Purpose-built for parallel texts (source + translation)

- Aligns source and target sentences

- Search both sides simultaneously

- Essential for translation studies

- More specialized than general tools

MONOCONC: Focused on monolingual concordancing with strong customization options

Web-Based Corpus Interfaces

Many large corpora are accessible through web interfaces, eliminating setup overhead.

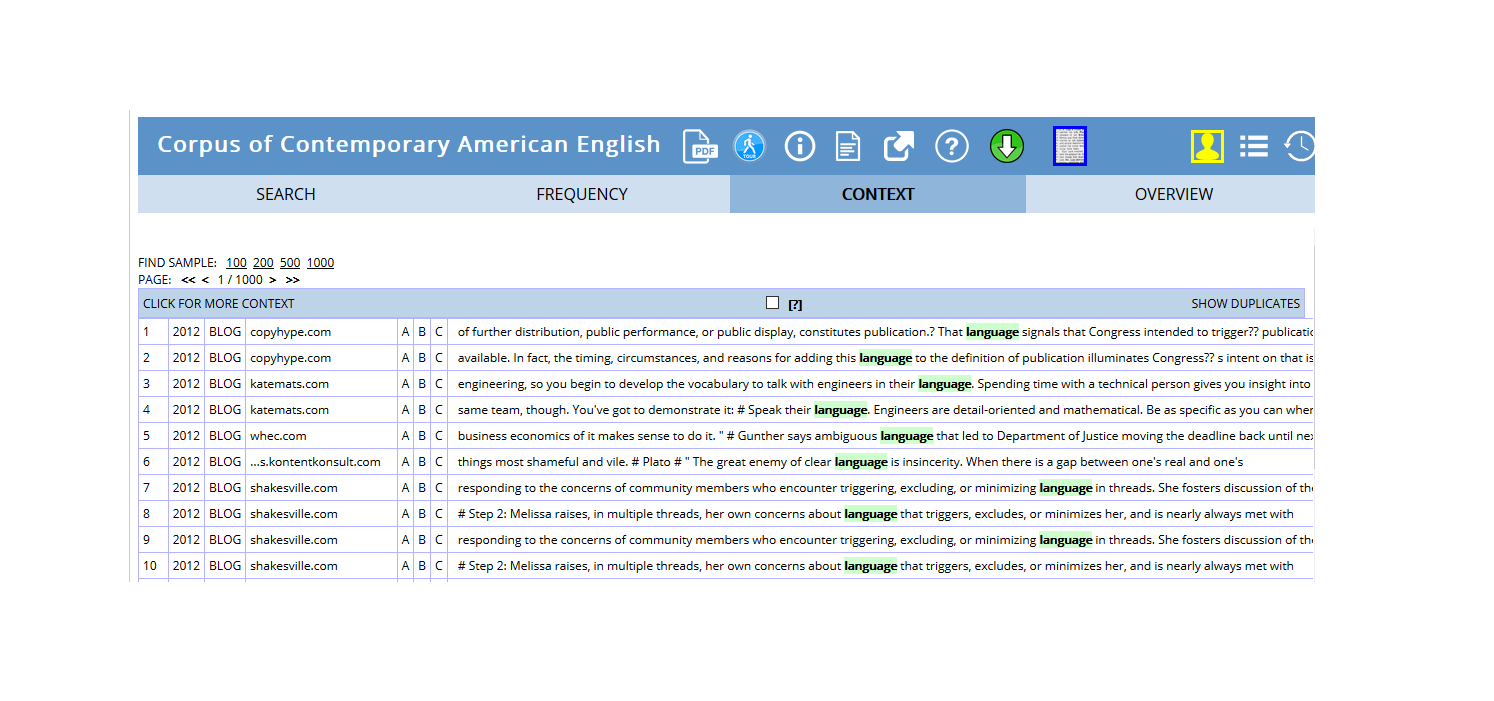

BYU Corpora Family

Mark Davies’s suite includes industry-standard reference corpora:

COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English):

- Over 1 billion words (1990-present)

- Balanced across genres (spoken, fiction, magazines, newspapers, academic)

- Updated annually

- Rich metadata for filtering

COHA (Corpus of Historical American English):

- 400+ million words (1820s-2000s)

- Track language change across two centuries

- Balanced by decade and genre

Other BYU Corpora:

- NOW Corpus (web, constantly updated)

- TV Corpus (soap operas)

- Movie Corpus

- Wikipedia Corpus

- And many more…

Strengths of BYU Corpora:

- Immediate access—no download or setup

- Professional corpus design

- Sophisticated search interface

- Metadata filtering (genre, date, etc.)

- Frequency/trend visualizations

- Free for academic use

When to use BYU Corpora:

- Quick checks of English usage

- Tracking diachronic change

- Comparing across genres

- Teaching with real data

- Exploring before building custom corpus

Limitations:

- Can’t upload your own texts

- English-focused (though some other languages available)

- Search options limited to interface

- Can’t save/export large result sets in free version

- Dependent on their corpus design decisions

COCA concordance for “language” showing genre distribution

Lextutor and Other Web Concordancers

Lextutor offers free web-based tools including concordancers, vocabulary profilers, and more.

When to use web concordancers:

- Classroom demonstrations (no installation)

- Quick vocabulary lookups

- Exploring concordancing concepts

- Public/shared computers

- Mobile devices

Programming-Based Solutions

For maximum flexibility, reproducibility, and integration with other analytical tools, programming languages offer unmatched power.

R with quanteda (Our Focus)

Why R and quanteda for concordancing:

Reproducibility:

- Scripts document every step

- Share exact methodology with colleagues

- Regenerate results precisely

- Satisfy open science requirements

- Version control with Git

Flexibility:

- Custom search patterns

- Unlimited filtering and grouping

- Integration with data manipulation (dplyr)

- Combine concordancing with statistics

- Automated workflows for large projects

Integration:

- Connect to databases

- Web scraping for corpus building

- Statistical modeling on results

- Machine learning pipelines

- Advanced visualization (ggplot2)

Scalability:

- Handle massive datasets

- Parallel processing for speed

- Cloud computing integration

- Automated batch processing

- Memory-efficient for large corpora

Cost:

- Completely free and open source

- No licensing fees ever

- Extensive package ecosystem

- Active development community

When to use R/quanteda:

- Reproducible research publications

- Complex analytical workflows

- Large-scale or custom corpora

- Integration with statistics/modeling

- Automated/repeating analyses

- When you need to document everything

Learning investment:

- Steeper initial learning curve than GUI tools

- Programming basics required

- But: transferable skills across research career

- Worth it for serious corpus work

- This tutorial will guide you!

Python with NLTK and Others

Python offers similar advantages through packages like NLTK, spaCy, and others.

When Python might be better:

- You already know Python

- Heavy NLP preprocessing needed

- Machine learning focus

- Web development integration

- You’re in a Python-centric community

For most linguistic concordancing, R/quanteda is excellent.

Features:

- Upload your own texts

- Pre-written code chunks (just click run)

- Modify code as you learn

- Download results (CSV, Excel)

- No installation needed

- Reproducible but accessible

When to use:

- Learning concordancing and coding together

- One-off analyses

- Quick results with your own texts

- Sharing with non-programmers

- Teaching hybrid approaches

Choosing the Right Tool

Different tasks call for different tools. Many researchers use multiple approaches:

Task

Recommended Tool

Why

Teaching basics

AntConc or Web interfaces

Zero barrier to entry, visual, immediate

Quick exploration

Web corpora (COCA, etc.)

No setup, instant results

Translation work

ParaConc or SketchEngine

Purpose-built for parallel texts

Publication research

WordSmith or R

Professional features, reproducibility

Large custom corpora

R/Python

Scalability, automation

Reproducible workflows

R/Python

Script everything, version control

Team projects

SketchEngine or R

Collaboration features

Learning to code

Our notebook tool

Gentle introduction

Pro tip: Start with AntConc or web interfaces to learn concepts, then graduate to R when you need more power or reproducibility.

Why Use R for Concordancing?

Given the excellent GUI tools available, why invest in learning R for concordancing?

The Reproducibility Imperative

Modern science increasingly demands reproducibility:

With GUI tools:

- “I opened AntConc, loaded corpus X, searched for Y, sorted by…”

- Hard to document exact steps

- Difficult for others to replicate

- Easy to forget what you did

With R scripts:

# Load corpus corpus <-readLines("my_texts.txt") # Create concordance kwic_result <- quanteda::kwic( tokens(corpus), pattern ="test_pattern", window =5) # Filter and arrange kwic_filtered <- kwic_result |>filter(str_detect(post, "specific_pattern")) |>arrange(pre) # Export write.csv(kwic_filtered, "results.csv")

Every step explicit

Exact replication possible

Share script with paper

Satisfies open science standards

Integration and Power

Seamless workflow:

# 1. Build corpus texts <-scrape_websites(urls) # 2. Concordance kwics <-kwic(tokens(texts), pattern) # 3. Statistical analysis collocation_test(kwics) # 4. Visualization ggplot(kwics) + ... # 5. Modeling regression_model <-lm(frequency ~ variables) # All in one environment!

vs. GUI approach:

- Export from concordancer

- Import to Excel

- Clean/rearrange

- Import to statistics software

- Export results

- Import to visualization tool

- Hope nothing was lost in translation!

Customization and Control

R allows:

- Custom search patterns beyond tool limitations

- Arbitrary filtering logic

- Novel analysis approaches

- Integration with your specific workflow

- Automation of repetitive tasks

- Handling of unusual data formats

Example: Complex filtering

# Find "must" but only: # - In questions # - Followed by a verb # - Not in negation # - In formal register # Easy in R, impossible/tedious in GUI tools

You don’t need to be a programmer - basic R suffices for concordancing, and you’ll learn by doing.

When GUI Tools Are Better

Use GUI tools when:

- Quick one-off exploration

- Teaching complete beginners

- Working with non-technical collaborators

- You need results immediately

- The analysis is truly simple

- Learning R isn’t worth it for this project

But consider R when:

- Doing serious research

- Need reproducibility

- Complex or custom analysis

- Working with large corpora

- Building a research program

- Want transferable skills

Exercise 2.1: Tool Comparison

Hands-On Tool Exploration

Task: Search for the same pattern in the same text using two different tools.

Choose a simple text (e.g., a news article)

Search for a word (e.g., “government”)

Try in:

AntConc (download and use)

A web concordancer (e.g., Lextutor)

OR our R notebook tool

Compare:

- Which was easiest to set up?

- Which gave you most control?

- Which had best export options?

- Which would you use for what purposes?

Discuss:

- What are the trade-offs?

- When would each be appropriate?

- What features matter most to you?

Part 3: Getting Started with R Concordancing

Now we’ll move from theory to practice, learning to create concordances using R and the quanteda package.

Benefits:

- Clear what dependencies you have

- Others can see what they need to install

- Easier to troubleshoot if something’s missing

- Professional script organization

# Good practice library(quanteda) library(dplyr) # ... rest of script # Poor practice # Code scattered throughout library(quanteda) # more code library(dplyr) # forgot earlier # more code

Loading Your First Text

We’ll use Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as our example text. This classic provides:

- Rich literary language

- Memorable characters and phrases

- Sufficient length for meaningful patterns

- Public domain (freely available)

Loading from Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg provides free access to thousands of public domain texts.

Code

# Load Alice's Adventures in Wonderland rawtext <-readLines("https://www.gutenberg.org/files/11/11-0.txt")

rawtext

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 11 ***

[Illustration]

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

by Lewis Carroll

THE MILLENNIUM FULCRUM EDITION 3.0

Contents

CHAPTER I. Down the Rabbit-Hole

CHAPTER II. The Pool of Tears

CHAPTER III. A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale

CHAPTER IV. The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill

CHAPTER V. Advice from a Caterpillar

CHAPTER VI. Pig and Pepper

CHAPTER VII. A Mad Tea-Party

CHAPTER VIII. The Queen’s Croquet-Ground

CHAPTER IX. The Mock Turtle’s Story

CHAPTER X. The Lobster Quadrille

CHAPTER XI. Who Stole the Tarts?

CHAPTER XII. Alice’s Evidence

CHAPTER I.

Down the Rabbit-Hole

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the

bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into

the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or

conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice

“without pictures or conversations?”

What just happened:

- readLines() fetched the text file from the web

- Each line became an element in a vector called rawtext

- We now have the complete book in R memory

Understanding the Raw Text Structure

Looking at the output, we see:

- Line 1-30: Title page, legal information, contents

- Real text starts: After “CHAPTER I”

- Formatting: Chapter headings, line breaks, spaces

This is typical of Project Gutenberg texts—they include metadata and formatting we need to handle.

Data Preparation: Cleaning the Text

Raw texts require preprocessing before analysis. This crucial step ensures clean, analysis-ready data.

Why Data Preparation Matters

The reality of text data:

- Downloaded texts include metadata (titles, licenses, etc.)

- Formatting varies (line breaks, spaces, special characters)

- Inconsistencies abound (encodings, punctuation)

- Structure needs standardization

Impact on analysis:

- Bad: Metadata contaminates results

- Bad: Formatting breaks pattern matching

- Bad: Inconsistencies cause missed matches

- Good: Clean data = reliable results

The 80/20 Rule of Text Analysis

Researchers often spend:

- 80% of time: Cleaning and preparing data

- 20% of time: Actually analyzing it

This isn’t wasted time—it’s essential investment. Poor preparation leads to unreliable results, wasted effort, and potentially wrong conclusions.

The payoff:

- Accurate results

- Reproducible analyses

- Confidence in findings

- Time saved troubleshooting later

Cleaning Alice in Wonderland

Let’s transform our raw text into analysis-ready format:

Code

text <- rawtext |># Collapse all lines into one continuous text paste0(collapse =" ") |># Remove extra white spaces (multiple spaces → single space) stringr::str_squish() |># Remove everything before "CHAPTER I." (title page, contents, etc.) stringr::str_remove(".*CHAPTER I\\.")

substr(text, start = 1, stop = 1000)

Down the Rabbit-Hole Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice “without pictures or conversations?” So she was considering in her own mind (as well as she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her. There was nothing so _very_ remarkable in that; nor did Alice think it so _very_ much out of the way to hear the Rabbit say to itself, “Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late!” (when she thought it over afterwards, it occurred to her that she ought to have wondered at this, but at the time it all seemed quite natural); but when the Rabbit actually _took a watch out of its waistcoat-pocke

What each step does:

1. paste0(collapse = " ")

- Joins all separate lines into one continuous string

- Why: Concordancing works better on continuous text

- Prevents artificial line-break effects on patterns

2. stringr::str_squish()

- Removes leading/trailing whitespace

- Reduces multiple spaces to single space

- Standardizes spacing throughout

3. stringr::str_remove(".*CHAPTER I\\.")

- Removes everything up to and including “CHAPTER I.”

- .* means “any characters”

- \\. means a literal period (escaped)

- Isolates the actual story text

Understanding the Regular Expression

The pattern ".*CHAPTER I\\." breaks down as:

. = any character

* = zero or more times

CHAPTER I = literal text

\\. = escaped period (. is special in regex)

Together: “Match any amount of any characters, followed by ‘CHAPTER I.’”

Regular expressions are powerful pattern-matching tools we’ll explore more later!

Exercise 3.1: Text Preparation Practice

Clean Your Own Text

Load a different Project Gutenberg text:

Code

# Example: Pride and Prejudice raw_pride <-readLines("https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1342/1342-0.txt")

Your tasks:

1. Examine the first 50 lines—what needs removing?

2. Find where the actual text starts (look for “Chapter” or similar)

3. Clean the text using the Alice example as a model

4. Verify your result looks correct

Questions:

- What patterns did you use to identify the start of the text?

- Were there any challenges specific to this text?

- How would you generalize this cleaning procedure?

Bonus: Write a function that automates Gutenberg text cleaning:

Code

clean_gutenberg <-function(url, start_pattern) { # Your code here }

Part 4: Creating Your First Concordance

Now that we have clean text, let’s extract our first concordances!

Basic KWIC Extraction

The kwic() function from quanteda makes concordancing straightforward.

Your First Concordance

Let’s search for “Alice”:

Code

mykwic <- quanteda::kwic( quanteda::tokens(text), # Tokenize the text first pattern = quanteda::phrase("Alice")) |># What to search for as.data.frame() # Convert to data frame

docname

from

to

pre

keyword

post

pattern

text1

4

4

Down the Rabbit-Hole

Alice

was beginning to get very

Alice

text1

63

63

a book , ” thought

Alice

“ without pictures or conversations

Alice

text1

143

143

in that ; nor did

Alice

think it so _very_ much

Alice

text1

229

229

and then hurried on ,

Alice

started to her feet ,

Alice

text1

299

299

In another moment down went

Alice

after it , never once

Alice

text1

338

338

down , so suddenly that

Alice

had not a moment to

Alice

Success! You’ve created your first concordance. Let’s understand what happened.

Understanding the kwic() Function

Function structure:

kwic( x =, # The tokenized text pattern =, # What to search for window =, # Context size (default: 5) ... # Other options )

Required arguments:

- x: Must be a tokens object (created by tokens())

- pattern: What you’re searching for

Important pattern specification:

- quanteda::phrase("Alice") = exact phrase (case-sensitive)

- Without phrase(), searches for individual tokens

- We’ll explore more pattern types soon!

The Concordance Table Structure

The result is a data frame with these columns:

Column

Contains

Purpose

docname

Document name

Track source (useful for multi-text corpora)

from

Start position

Where match begins (token number)

to

End position

Where match ends

pre

Left context

Words before the keyword

keyword

The match

Your search term

post

Right context

Words after the keyword

pattern

Search pattern

What you searched for (useful when searching multiple patterns)

Exploring Your Concordance

How many matches did we find?

Code

nrow(mykwic) # Count rows

[1] 386

OR

Code

length(mykwic$keyword) # Count keywords

[1] 386

We found 386 instances of “Alice” in the text!

What variations were found?

Code

table(mykwic$keyword)

Alice

386

All instances are exactly “Alice” (case-sensitive match).

Adjusting the Context Window

The default context is 5 words on each side. Sometimes you need more:

“ without pictures or conversations ? ” So she was

alice

text1

143

143

was nothing so _very_ remarkable in that ; nor did

Alice

think it so _very_ much out of the way to

alice

text1

229

229

and looked at it , and then hurried on ,

Alice

started to her feet , for it flashed across her

alice

text1

299

299

rabbit-hole under the hedge . In another moment down went

Alice

after it , never once considering how in the world

alice

text1

338

338

, and then dipped suddenly down , so suddenly that

Alice

had not a moment to think about stopping herself before

alice

When to use wider windows:

- Understanding full sentence context

- Analyzing longer constructions

- Studying distant relationships

- Literary analysis requiring more text

When to use narrower windows:

- Focused on immediate collocates

- Large result sets (easier to scan)

- Identifying local patterns

- Quick exploration

Choosing Context Window Size

General guidelines:

- 5 words (default): Good starting point for most analyses

- 3 words: Immediate collocates, tight focus

- 10-15 words: Sentence-level context

- 20+ words: Paragraph-level context (rare, usually too much)

Experiment! Try different sizes and see what reveals patterns best for your research question.

Exercise 4.1: Basic Concordancing Practice

Your Turn!

Using the Alice text, complete these tasks:

1. Extract concordances for “confused”

Answer

Code

kwic_confused <- quanteda::kwic( x = quanteda::tokens(text), pattern = quanteda::phrase("confused") ) # Display first 10 kwic_confused |>as.data.frame() |>head(10)

docname from to pre keyword

1 text1 6217 6217 , calling out in a confused

2 text1 19140 19140 . ” This answer so confused

3 text1 19325 19325 said Alice , very much confused

4 text1 33422 33422 she knew ) to the confused

post pattern

1 way , “ Prizes ! confused

2 poor Alice , that she confused

3 , “ I don’t think confused

4 clamour of the busy farm-yard—while confused

2. How many times does “wondering” appear?

Answer

Code

quanteda::kwic( x = quanteda::tokens(text), pattern = quanteda::phrase("wondering") ) |>as.data.frame() |>nrow()

[1] 7

There are 7 instances.

3. Extract “strange” with a 7-word window, show first 5 lines

docname from to pre keyword

1 text1 3527 3527 , but her voice sounded hoarse and strange

2 text1 13147 13147 right size , that it felt quite strange

3 text1 32997 32997 she could remember them , all these strange

4 text1 33204 33204 place around her became alive with the strange

5 text1 33514 33514 eyes bright and eager with many a strange

post pattern

1 , and the words did not come strange

2 at first ; but she got used strange

3 Adventures of hers that you have just strange

4 creatures of her little sister’s dream . strange

5 tale , perhaps even with the dream strange

Challenge: Pick your own word and explore different window sizes. Which size reveals the most about how the word is used?

Part 5: Exporting and Saving Concordances

Once you’ve created concordances, you’ll often want to save them for further analysis, sharing, or documentation.

Exporting to Excel

Excel spreadsheets are widely compatible and easy to share with colleagues.

Code

# Export to Excel write_xlsx(mykwic, here::here("my_alice_concordance.xlsx"))

What this does:

- write_xlsx() creates an Excel file (.xlsx)

- here::here() saves it in your working directory

- Result: A spreadsheet with all concordance data

Using here() for File Paths

The here package makes file paths easier and more portable:

Code

# Without here - breaks if you move project write_xlsx(data, "C:/Users/YourName/Documents/project/file.xlsx") # With here - works anywhere write_xlsx(data, here::here("file.xlsx")) # Subdirectories write_xlsx(data, here::here("output", "results", "file.xlsx"))

Benefits:

- Works on Windows, Mac, Linux

- No hard-coded paths

- Project-relative paths

- Collaborators can run your code

Other Export Formats

Code

# CSV (universal, simple) write.csv(mykwic, here::here("concordance.csv"), row.names =FALSE) # Tab-separated (good for large texts) write.table(mykwic, here::here("concordance.txt"), sep ="\t", row.names =FALSE) # R data format (preserves all R attributes) saveRDS(mykwic, here::here("concordance.rds")) # Load RDS back later mykwic_loaded <-readRDS(here::here("concordance.rds"))

When to use each:

Format

Best For

Why

Excel (.xlsx)

Sharing with non-R users

Widely compatible, can open directly

CSV

Simple data exchange

Universal, plain text, version control friendly

TSV/TXT

Very large datasets

Smaller file size than Excel

RDS

R-to-R sharing

Preserves all object attributes, efficient

Creating Export-Ready Tables

For presentations or reports, format your concordances nicely:

Code

# Create a nicely formatted subset mykwic |>head(20) |># First 20 for manageable size select(pre, keyword, post) |># Just the interesting columns flextable() |>set_caption("Concordance of 'Alice' in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland") |>theme_zebra() |>autofit() |>save_as_docx(path = here::here("concordance_table.docx"))

This creates a Word document with a professional-looking table—perfect for embedding in papers!

Part 6: Advanced Pattern Matching

Multi-Word Expressions and Phrases

While single words are common search targets, language research often requires extracting phrases or multi-word expressions (MWEs).

Why Multi-Word Expressions Matter

Language is more than individual words:

- Idioms: “kick the bucket”, “spill the beans”

- Collocations: “strong coffee”, “make a decision”

- Fixed expressions: “by and large”, “as a matter of fact”

- Titles and names: “Mad Hatter”, “Cheshire Cat”

- Technical terms: “global warming”, “machine learning”

These MWEs often function as single semantic units despite containing multiple words. Searching for individual words misses the unified meaning.

Extracting Phrases with quanteda

The phrase() function tells quanteda to treat multiple words as a single search unit:

Code

# Search for "poor alice" as a phrase kwic_pooralice <- quanteda::kwic( quanteda::tokens(text), pattern = quanteda::phrase("poor alice")) |>as.data.frame()

docname

from

to

pre

keyword

post

pattern

text1

1,541

1,542

go through , ” thought

poor Alice

, “ it would be

poor alice

text1

2,130

2,131

; but , alas for

poor Alice

! when she got to

poor alice

text1

2,332

2,333

use now , ” thought

poor Alice

, “ to pretend to

poor alice

text1

2,887

2,888

to the garden door .

Poor Alice

! It was as much

poor alice

text1

3,604

3,605

right words , ” said

poor Alice

, and her eyes filled

poor alice

text1

6,876

6,877

mean it ! ” pleaded

poor Alice

. “ But you’re so

poor alice

text1

7,290

7,291

more ! ” And here

poor Alice

began to cry again ,

poor alice

text1

8,239

8,240

at home , ” thought

poor Alice

, “ when one wasn’t

poor alice

text1

11,788

11,789

to it ! ” pleaded

poor Alice

in a piteous tone .

poor alice

text1

19,141

19,142

” This answer so confused

poor Alice

, that she let the

poor alice

What phrase() does:

- Treats “poor alice” as an inseparable unit

- Both words must appear consecutively

- Respects word boundaries

- Case-sensitive by default

Without phrase():

Code

# This would match "poor" and "alice" separately, anywhere in the text kwic(tokens(text), pattern =c("poor", "alice"))

Case Sensitivity Control

By default, searches are case-sensitive. Control this behavior:

Use case-insensitive when:

- Names might be capitalized variably

- Sentence-initial position matters

- Historical texts with inconsistent capitalization

- You want all variants regardless of position

Keep case-sensitive when:

- Proper names vs. common words matter (e.g., “Apple” vs. “apple”)

- You’re studying capitalization patterns

- Precision is more important than recall

Searching Multiple Phrases

Search for several phrases simultaneously:

Code

# Search for multiple character descriptions patterns <-c("poor alice", "little alice", "dear alice") kwic_alice_variants <- quanteda::kwic( quanteda::tokens(text), pattern =phrase(patterns) ) |>as.data.frame() # See which variants were found table(kwic_alice_variants$keyword)

docname from to pre keyword

1 text1 16576 16577 wish I’d gone to see the Hatter

2 text1 16607 16608 and the March Hare and the Hatter

3 text1 16859 16860 wants cutting , ” said the Hatter

4 text1 16905 16906 it’s very rude . ” The Hatter

5 text1 17049 17050 a bit ! ” said the Hatter

6 text1 17174 17175 with you , ” said the Hatter

7 text1 17209 17210 , which wasn’t much . The Hatter

8 text1 17287 17288 days wrong ! ” sighed the Hatter

9 text1 17338 17339 in as well , ” the Hatter

10 text1 17453 17454 should it ? ” muttered the Hatter

post pattern

1 instead ! ” CHAPTER VII the hatter

2 were having tea at it the hatter

3 . He had been looking the hatter

4 opened his eyes very wide the hatter

5 . “ You might just the hatter

6 , and here the conversation the hatter

7 was the first to break the hatter

8 . “ I told you the hatter

9 grumbled : “ you shouldn’t the hatter

10 . “ Does _your_ watch the hatter

docname from to pre keyword post

1 text1 932 933 ! ” ( Dinah was the cat . ) “ I hope

2 text1 15624 15625 a few yards off . The Cat only grinned when it saw

3 text1 15749 15750 get to , ” said the Cat . “ I don’t much

4 text1 15775 15776 you go , ” said the Cat . “ — so long

5 text1 15805 15806 do that , ” said the Cat , “ if you only

pattern

1 the cat

2 the cat

3 the cat

4 the cat

5 the cat

Challenge: Find all instances of character names with titles (e.g., “the Duchess”, “the King”, “the Queen”). How would you search for these patterns efficiently?

Part 7: Regular Expressions for Power Users

Regular expressions (regex) provide powerful pattern-matching capabilities beyond exact words or phrases.

Understanding Regular Expressions

A regular expression is a sequence of characters that describes a search pattern. Think of it as a wildcard on steroids.

Why Regular Expressions Matter

Without regex:

- Search for “walk”, “walks”, “walked”, “walking” separately

- Four searches, combine results manually

- Miss any variants you didn’t think of

With regex:

- "walk.*" finds all forms in one search

- Captures “walks”, “walked”, “walking”, “walker”, etc.

- Systematic, comprehensive

Regular Expression Types

There are three fundamental categories:

1. Symbols for Frequencies

These control how many times a pattern appears:

Symbol

Explanation

Example

?

Preceding item is optional (0 or 1 times)

walk[a-z]? → walk, walks

*

Preceding item appears 0 or more times

walk[a-z]* → walk, walks, walked, walking

+

Preceding item appears 1 or more times

walk[a-z]+ → walks, walked, walking (not walk)

{n}

Preceding item appears exactly n times

walk[a-z]{2} → walked

{n,}

Preceding item appears n or more times

walk[a-z]{2,} → walked, walking

{n,m}

Preceding item appears n to m times

walk[a-z]{2,3} → walked, walking

2. Character Classes

These represent groups of characters:

Symbol

Explanation

[ab]

Lowercase a or b

[AB]

Uppercase A or B

[12]

Digits 1 or 2

[:digit:]

Any digit: 0-9

[:lower:]

Any lowercase letter: a-z

[:upper:]

Any uppercase letter: A-Z

[:alpha:]

Any letter: a-z, A-Z

[:alnum:]

Any letter or digit

[:punct:]

Any punctuation character

[:space:]

Any whitespace (space, tab, newline)

.

Any single character (wildcard)

3. Position Anchors

These specify where patterns must appear:

Symbol

Explanation

\\b

Word boundary (start or end of word)

\\B

Not a word boundary (inside a word)

^

Start of string/line

$

End of string/line

<

Start of word

>

End of word

Using Regular Expressions in Concordancing

To use regex in kwic(), set valuetype = "regex":

Code

# Find words starting with "alic" OR "hatt" patterns <-"\\b(alic|hatt).*"kwic_regex <- quanteda::kwic( quanteda::tokens(text), pattern = patterns, valuetype ="regex") |>as.data.frame()

docname

from

to

pre

keyword

post

pattern

text1

4

4

Down the Rabbit-Hole

Alice

was beginning to get very

\b(alic|hatt).*

text1

63

63

a book , ” thought

Alice

“ without pictures or conversations

\b(alic|hatt).*

text1

143

143

in that ; nor did

Alice

think it so _very_ much

\b(alic|hatt).*

text1

229

229

and then hurried on ,

Alice

started to her feet ,

\b(alic|hatt).*

text1

299

299

In another moment down went

Alice

after it , never once

\b(alic|hatt).*

text1

338

338

down , so suddenly that

Alice

had not a moment to

\b(alic|hatt).*

text1

521

521

“ Well ! ” thought

Alice

to herself , “ after

\b(alic|hatt).*

text1

647

647

for , you see ,

Alice

had learnt several things of

\b(alic|hatt).*

text1

719

719

got to ? ” (

Alice

had no idea what Latitude

\b(alic|hatt).*

text1

910

910

else to do , so

Alice

soon began talking again .

\b(alic|hatt).*

Pattern breakdown:

- \\b = word boundary (start of word)

- (alic|hatt) = either “alic” OR “hatt”

- .* = followed by any characters

- Result: “alice”, “hatter”, “hatters” but NOT “malice” or “shatter”

Common Regex Patterns for Concordancing

Find all forms of a word:

Code

# All forms of "think" kwic(tokens(text), pattern ="\\bthink.*", valuetype ="regex") # Matches: think, thinks, thinking, thought, thinker # Words ending in "ing" kwic(tokens(text), pattern =".*ing\\b", valuetype ="regex") # Words ending in "tion" kwic(tokens(text), pattern =".*tion\\b", valuetype ="regex")

Find words of specific length:

Code

# Three-letter words kwic(tokens(text), pattern ="\\b[a-z]{3}\\b", valuetype ="regex") # Words 10+ letters long kwic(tokens(text), pattern ="\\b[a-z]{10,}\\b", valuetype ="regex")

Find patterns with specific structure:

Code

# Words with double letters kwic(tokens(text), pattern ="\\b\\w*(.)\\1\\w*\\b", valuetype ="regex") # Matches: little, bottle, matters, etc. # Words starting with vowels kwic(tokens(text), pattern ="\\b[aeiou]\\w*", valuetype ="regex")

Regex Can Be Tricky!

Regular expressions are powerful but can be:

- Cryptic: \\b(?:alic|hatt).* looks like gibberish at first

- Fragile: Small changes can break patterns

- Surprising: They might match more (or less) than you expect

Best practices:

- Test patterns on small samples first

- Use online regex testers (regex101.com)

- Comment your patterns explaining what they do

- Start simple, add complexity gradually

- Check results carefully—regex can surprise you!

[1] docname from to pre keyword post pattern

<0 rows> (or 0-length row.names)

2. How many words begin with “pit”?

Answer

Code

quanteda::kwic( x = quanteda::tokens(text), pattern ="\\bpit.*", valuetype ="regex") |>as.data.frame() |>nrow()

[1] 5

3. Find words ending in “ption” (first 5)

Answer

Code

quanteda::kwic( x = quanteda::tokens(text), pattern =".*ption\\b", valuetype ="regex") |>as.data.frame() |>head(5)

docname from to pre keyword

1 text1 5775 5775 adjourn , for the immediate adoption

post pattern

1 of more energetic remedies — .*ption\\b

Challenge:

1. Find all words starting with “un-” (negative prefix)

2. Find all words with exactly 4 letters

3. Find all words containing “qu”

4. Find words that appear to be capitalized names (hint: uppercase start)

Part 8: Filtering and Refining Concordances

Raw concordances are just the starting point. The real power comes from filtering, sorting, and refining results to reveal patterns.

Piping for Conditional Concordances

Often we want concordances only when specific conditions are met. Piping with dplyr makes this elegant.

The Pipe Operator: |> or %>%

Piping chains operations together: “do this, then do that”

Code

# Without piping (nested, hard to read) filter(as.data.frame(kwic(tokens(text), "alice")), condition) # With piping (clear, sequential) kwic(tokens(text), "alice") |>as.data.frame() |>filter(condition) # Read as: "take text, make concordance, convert to dataframe, filter"

Filtering by Context

Find “alice” only when preceded by “poor” or “little”:

Code

quanteda::kwic( x = quanteda::tokens(text), pattern ="alice") |>as.data.frame() |># Filter: "pre" column must end with "poor" or "little" dplyr::filter(stringr::str_detect(pre, "poor$|little$")) -> kwic_pipe

docname

from

to

pre

keyword

post

pattern

text1

1,542

1,542

through , ” thought poor

Alice

, “ it would be

alice

text1

1,725

1,725

” but the wise little

Alice

was not going to do

alice

text1

2,131

2,131

but , alas for poor

Alice

! when she got to

alice

text1

2,333

2,333

now , ” thought poor

Alice

, “ to pretend to

alice

text1

3,605

3,605

words , ” said poor

Alice

, and her eyes filled

alice

text1

6,877

6,877

it ! ” pleaded poor

Alice

. “ But you’re so

alice

text1

7,291

7,291

! ” And here poor

Alice

began to cry again ,

alice

text1

8,240

8,240

home , ” thought poor

Alice

, “ when one wasn’t

alice

text1

11,789

11,789

it ! ” pleaded poor

Alice

in a piteous tone .

alice

text1

19,142

19,142

This answer so confused poor

Alice

, that she let the

alice

Pattern breakdown:

- str_detect(pre, "poor$|little$")

- Check if pre (preceding context) contains…

- poor$ = “poor” at the end ($ = end anchor)

- | = OR

- little$ = “little” at the end

Why the $ matters:

- "poor$" = must be last word before keyword

- "poor" = anywhere in preceding context

- Precision prevents false matches like “poorly alice”

Multiple Conditions

Combine filters for complex queries:

Code

kwic(tokens(text), "said") |>as.data.frame() |># Must be preceded by name AND followed by specific punctuation filter( str_detect(pre, "Alice$|Hatter$|Queen$"), str_detect(post, "^,|^\\.") )

This finds speech acts: “[Character] said, …”

Filtering by Position

Find instances only at specific positions in the text:

Code

kwic(tokens(text), "alice") |>as.data.frame() |># Only in first 1000 tokens filter(from <=1000) # Only in last quarter of text max_position <-max(from) kwic_data |>filter(from >= max_position *0.75)

Sorting and Arranging Concordances

Reordering concordances reveals patterns invisible in occurrence order.

Alphabetical Sorting

Sort by what follows the keyword:

Code

quanteda::kwic( x = quanteda::tokens(text), pattern ="alice") |>as.data.frame() |># Arrange alphabetically by following context dplyr::arrange(post) -> kwic_ordered

docname

from

to

pre

keyword

post

pattern

text1

7,754

7,754

happen : “ ‘ Miss

Alice

! Come here directly ,

alice

text1

2,888

2,888

the garden door . Poor

Alice

! It was as much

alice

text1

2,131

2,131

but , alas for poor

Alice

! when she got to

alice

text1

30,891

30,891

voice , the name “

Alice

! ” CHAPTER XII .

alice

text1

8,423

8,423

“ Oh , you foolish

Alice

! ” she answered herself

alice

text1

2,606

2,606

and curiouser ! ” cried

Alice

( she was so much

alice

text1

25,861

25,861

I haven’t , ” said

Alice

) — “ and perhaps

alice

text1

32,275

32,275

explain it , ” said

Alice

, ( she had grown

alice

text1

32,843

32,843

for you ? ” said

Alice

, ( she had grown

alice

text1

1,678

1,678

here before , ” said

Alice

, ) and round the

alice

Why sort alphabetically?

- Groups similar contexts together

- Reveals collocational patterns

- Makes manual analysis easier

- Identifies semantic prosody

Sort by different columns:

Code

arrange(pre) # By preceding context arrange(keyword) # By matched pattern (if searching multiple) arrange(from) # By position in text (chronological)

Sorting by Frequency

More powerful: arrange by how common collocates are.

Step-by-Step Frequency Sorting

Code

quanteda::kwic( x = quanteda::tokens(text), pattern ="alice") |>as.data.frame() |># Extract first word after keyword dplyr::mutate(post1 =str_remove_all(post, " .*")) |># Group by that word dplyr::group_by(post1) |># Count frequency of each dplyr::mutate(post1_freq =n()) |># Sort by frequency (descending) dplyr::arrange(-post1_freq) -> kwic_ordered_coll

docname

from

to

pre

keyword

post

pattern

post1

post1_freq

text1

1,542

1,542

through , ” thought poor

Alice

, “ it would be

alice

,

78

text1

1,678

1,678

here before , ” said

Alice

, ) and round the

alice

,

78

text1

2,333

2,333

now , ” thought poor

Alice

, “ to pretend to

alice

,

78

text1

2,410

2,410

eat it , ” said

Alice

, “ and if it

alice

,

78

text1

2,739

2,739

to them , ” thought

Alice

, “ or perhaps they

alice

,

78

text1

2,945

2,945

of yourself , ” said

Alice

, “ a great girl

alice

,

78

text1

3,605

3,605

words , ” said poor

Alice

, and her eyes filled

alice

,

78

text1

3,751

3,751

oh dear ! ” cried

Alice

, with a sudden burst

alice

,

78

text1

3,918

3,918

narrow escape ! ” said

Alice

, a good deal frightened

alice

,

78

text1

4,181

4,181

so much ! ” said

Alice

, as she swam about

alice

,

78

What each step does:

mutate(post1 = str_remove_all(post, " .*"))

Creates new column post1

Extracts just the first word after keyword

Removes everything after first space

group_by(post1)

Groups all rows with same following word

Enables per-group calculations

mutate(post1_freq = n())

Counts how many in each group

n() returns group size

Adds frequency to each row

arrange(-post1_freq)

Sorts by frequency

- means descending (highest first)

Most common collocates appear first

Why frequency sorting matters:

- Reveals strongest collocational patterns

- Identifies typical vs. unusual usage

- Quantifies intuitions

- Prioritizes analysis (examine common patterns first)

Multi-Level Sorting

Sort by multiple criteria:

Code

kwic_data |>arrange(-post1_freq, -post2_freq, pre1) # Read as: "sort by post1 frequency (desc), # then post2 frequency (desc), # then pre1 (ascending)"

Extracting N-grams Around Keywords

Sometimes you want to analyze not just the next word, but the next 2-3 words (bigrams, trigrams).

Code

mykwic |>rowwise() |>mutate( # First word after post1 =unlist(strsplit(post, " "))[1], # Second word after post2 =unlist(strsplit(post, " "))[2], # Third word after post3 =unlist(strsplit(post, " "))[3], # Last word before pre1 =tail(unlist(strsplit(pre, " ")), 1), # Second-to-last before pre2 =tail(unlist(strsplit(pre, " ")), 2)[1], # Third-to-last before pre3 =tail(unlist(strsplit(pre, " ")), 3)[1] )

This creates columns for analyzing collocational patterns at different distances.

Exercise 8.1: Filtering and Sorting

Advanced Concordance Manipulation

Using the Alice text:

1. Find “said” preceded by a character name

Hint: Filter for names ending the pre context

Answer

Code

quanteda::kwic( x = quanteda::tokens(text), pattern ="said") |>as.data.frame() |>filter(str_detect(pre, "Alice$|Hatter$|Queen$|King$|Cat$")) |>head(10)

docname from to pre keyword

1 text1 7715 7715 it seems , ” Alice said

2 text1 11677 11677 said the Caterpillar . Alice said

3 text1 14187 14187 that soup ! ” Alice said

4 text1 14421 14421 that do , ” Alice said

5 text1 15850 15850 direction , ” the Cat said

6 text1 16894 16894 personal remarks , ” Alice said

7 text1 17618 17618 yet ? ” the Hatter said

8 text1 17747 17747 don’t ! ” the Hatter said

9 text1 18857 18857 go on ! ” Alice said

10 text1 19107 19107 the well , ” Alice said

post pattern

1 to herself , “ to said

2 nothing : she had never said

3 to herself , as well said

4 very politely , feeling quite said

5 , waving its right paw said

6 with some severity ; “ said

7 , turning to Alice again said

8 , tossing his head contemptuously said

9 very humbly ; “ I said

10 to the Dormouse , not said

2. Sort “and” concordances by preceding word frequency

# A tibble: 10 × 9

# Groups: pre1 [1]

docname from to pre keyword post pattern pre1 pre1_freq

<chr> <int> <int> <chr> <chr> <chr> <fct> <chr> <int>

1 text1 20 20 sister on the bank… and of h… and <NA> 642

2 text1 52 52 conversations in i… and what… and <NA> 642

3 text1 219 219 out of its waistco… and look… and <NA> 642

4 text1 224 224 and looked at it , and then… and <NA> 642

5 text1 263 263 take out of it , and burn… and <NA> 642

6 text1 276 276 the field after it… and fort… and <NA> 642

7 text1 329 329 tunnel for some wa… and then… and <NA> 642

8 text1 431 431 sides of the well , and noti… and <NA> 642

9 text1 662 662 lessons in the sch… and thou… and <NA> 642

10 text1 840 840 or Australia ? ” ( and she … and <NA> 642

Challenge: Find all instances of “very” followed by an adjective. How would you identify adjectives? (Hint: might need manual classification or a part-of-speech tagger)

Part 9: Working with Transcripts

Spoken language transcripts require special handling due to their unique features: speaker turns, pauses, laughter, overlaps, and other paralinguistic information.

Understanding Transcript Structure

Transcripts differ from written texts in important ways:

Written text:

- Continuous prose

- Standard punctuation

- Paragraph structure

- Edited and polished

<S1A-001$A> <#> Well how did the riding go tonight

<S1A-001$B> <#> It was good so it was <#> Just I I couldn't believe that she was going to let me jump <,> that was only the fourth time you know <#> It was great <&> laughter </&>

<S1A-001$A> <#> What did you call your horse

<S1A-001$B> <#> I can't remember <#> Oh Mary 's Town <,> oh

<S1A-001$A> <#> And how did Mabel do

<S1A-001$B> <#> Did you not see her whenever she was going over the jumps <#> There was one time her horse refused and it refused three times <#> And then <,> she got it round and she just lined it up straight and she just kicked it and she hit it with the whip <,> and over it went the last time you know <#> And Stephanie told her she was very determined and very well-ridden <&> laughter </&> because it had refused the other times you know <#> But Stephanie wouldn't let her give up on it <#> She made her keep coming back and keep coming back <,> until <,> it jumped it you know <#> It was good

<S1A-001$A> <#> Yeah I 'm not so sure her jumping 's improving that much <#> She uh <,> seemed to be holding the reins very tight

Transcript features visible:

- <S1A-001 Riding> = Header with file ID and title

- <I> = Transcript start marker

- <S1A-001$A> = Speaker A in file 001, section S1A

- <#> = Speech unit boundary

- <,> = Pause

- <&> laughter </&> = Paralinguistic information

Preprocessing Transcripts

Transcripts need different preprocessing than written texts.

Remove:

- Headers and metadata (usually)

- Markup that interferes with searching

- Excess spacing

It depends on your research question!

Collapsing Transcripts

For basic concordancing, collapse into continuous text:

Code

transcripts_collapsed <-sapply(files, function(x) { x <-readLines(x) # Collapse all lines together x <-paste0(x, collapse =" ") # Clean up spacing x <-str_squish(x) })

<S1A-001 Riding> <I> <S1A-001$A> <#> Well how did the riding go tonight <S1A-001$B> <#> It was good so it was <#> Just I I couldn't believe that she was going to let me jump <,> that was only the fourth time you know <#> It was great <&> laughter </&> <S1A-001$A> <#> What did you call your horse <S1A-001$B> <#> I can't remember <#> Oh Mary 's Town <,> oh <S1A-001$A> <#> And how did Mabel do <S1A-001$B> <#> Did you not see her whenever she was going over the jumps <#> There was one time her horse

<S1A-002 Dinner chat 1> <I> <S1A-002$A> <#> He 's been married for three years and is now <{> <[> getting divorced </[> <S1A-002$B> <#> <[> No no </[> </{> he 's got married last year and he 's getting <{> <[> divorced </[> <S1A-002$A> <#> <[> He 's now </[> </{> getting divorced <S1A-002$C> <#> Just right <S1A-002$D> <#> A wee girl of her age like <S1A-002$E> <#> Well there was a guy <S1A-002$C> <#> How long did she try it for <#> An hour a a year <S1A-002$B> <#> Mhm <{> <[> mhm </[> <S1A-002$E

<S1A-003 Dinner chat 2> <I> <S1A-003$A> <#> I <.> wa </.> I want to go to Peru but uh <S1A-003$B> <#> Do you <S1A-003$A> <#> Oh aye <S1A-003$B> <#> I 'd love to go to Peru <S1A-003$A> <#> I want I want to go up the Machu Picchu before it falls off the edge of the mountain <S1A-003$B> <#> Lima 's supposed to be a bit dodgy <S1A-003$A> <#> Mm <S1A-003$B> <#> Bet it would be <S1A-003$B> <#> Mm <S1A-003$A> <#> But I I just I I would like <,> Machu Picchu is collapsing <S1A-003$B> <#> I don't know wh

<S1A-004 Nursing home 1> <I> <S1A-004$A> <#> Honest to God <,> I think the young ones <#> Sure they 're flying on Monday in I think it 's Shannon <#> This is from Texas <S1A-004$B> <#> This English girl <S1A-004$A> <#> The youngest one <,> the dentist <,> she 's married to the dentist <#> Herself and her husband <,> three children and she 's six months pregnant <S1A-004$C> <#> Oh God <S1A-004$B> <#> And where are they going <S1A-004$A> <#> Coming to Dublin to the mother <{> <[> or <unclear> 3 sy

<S1A-005 Masons> <I> <S1A-005$A> <#> Right shall we risk another beer or shall we try and <,> <{> <[> ride the bikes down there or do something like that </[> <S1A-005$B> <#> <[> Well <,> what about the </[> </{> provisions <#> What time <{> <[> <unclear> 4 sylls </unclear> </[> <S1A-005$C> <#> <[> Is is your </[> </{> man coming here <S1A-005$B> <#> <{> <[> Yeah </[> <S1A-005$A> <#> <[> He said </[> </{> he would meet us here <S1A-005$B> <#> Just the boat 's arriving you know a few minutes ' wa

Concordancing Transcripts

Now extract concordances, being mindful of markup:

Code

kwic_trans <- quanteda::kwic( # Tokenize by whitespace to preserve markup quanteda::tokens(transcripts_collapsed, what ="fasterword"), # Search for "you know" pattern = quanteda::phrase("you know"), # Wider context for spoken language window =10) |>as.data.frame() |># Clean up file names dplyr::mutate(docname =str_replace_all(docname, ".*/(.*?).txt", "\\1"))

docname

from

to

pre

keyword

post

pattern

S1A-001

42

43

let me jump <,> that was only the fourth time

you know

<#> It was great <&> laughter </&> <S1A-001$A> <#> What

you know

S1A-001

140

141

the whip <,> and over it went the last time

you know

<#> And Stephanie told her she was very determined and

you know

S1A-001

164

165

<&> laughter </&> because it had refused the other times

you know

<#> But Stephanie wouldn't let her give up on it

you know

S1A-001

193

194

and keep coming back <,> until <,> it jumped it

you know

<#> It was good <S1A-001$A> <#> Yeah I 'm not

you know

S1A-001

402

403

'd be far better waiting <,> for that one <,>

you know

and starting anew fresh <S1A-001$A> <#> Yeah but I mean

you know

S1A-001

443

444

the best goes top of the league <,> <{> <[>

you know

</[> <S1A-001$A> <#> <[> So </[> </{> it 's like

you know

S1A-001

484

485

I 'm not sure now <#> We didn't discuss it

you know

<S1A-001$A> <#> Well it sounds like more money <S1A-001$B> <#>

you know

S1A-001

598

599

on Monday and do without her lesson on Tuesday <,>

you know

<#> But I was keeping her going cos I says

you know

S1A-001

727

728

to take it tomorrow <,> that she could take her

you know

the wee shoulder bag she has <S1A-001$A> <#> Mhm <S1A-001$B>

you know

S1A-001

808

809

<,> and <,> sort of show them around <,> uhm

you know

their timetable and <,> give them their timetable and show

you know

Key considerations:

what = "fasterword"

- Tokenizes by whitespace

- Preserves tags like <#>, <,>

- Alternative to default tokenization

Wider window (10 tokens)

- Spoken language has more fillers, pauses

- Need more context to understand utterance

- Captures more of the conversational flow

Why study “you know”?

- Discourse marker in spoken English

- Not about knowledge—about interaction

- Signals common ground, turn-taking

- Varies by speaker, context, genre

Analyzing Speaker Patterns

Extract concordances by speaker:

Code

# First, extract speaker IDs into a separate column kwic_trans |>mutate( # Extract speaker ID from preceding context speaker =str_extract(pre, "<S1A-[0-9]+\\$[A-Z]>") ) |># Analyze by speaker group_by(speaker) |>summarize( count =n(), per_1000_words = count / (total_words /1000) )

This reveals which speakers use “you know” most frequently—useful for sociolinguistic analysis!

Part 10: Custom Concordance Functions

While quanteda’s kwic() is excellent, sometimes you need custom functionality. Building your own concordance function teaches how concordancing works under the hood.

Understanding Concordance Mechanics

What kwic() does internally:

1. Find positions where pattern matches

2. Calculate context window boundaries

3. Extract text at those positions

4. Format as table

Key differences from quanteda:

- Uses characters not tokens for context

- More control over exact boundaries

- Can customize any aspect

- Educational: see how it works!

Using the Custom Function

Code

# Search for "you know" with 50-character context kwic_youknow <-mykwic(transcripts_collapsed, "you know", 50)

Id

PrecedingContext

Token

SubsequentContext

1

to let me jump <,> that was only the fourth time

you know

<#> It was great <&> laughter </&> <S1A-001$A> <#

2

with the whip <,> and over it went the last time

you know

<#> And Stephanie told her she was very determine

3

ghter </&> because it had refused the other times

you know

<#> But Stephanie wouldn't let her give up on it

4

k and keep coming back <,> until <,> it jumped it

you know

<#> It was good <S1A-001$A> <#> Yeah I 'm not so

5

she 'd be far better waiting <,> for that one <,>

you know

and starting anew fresh <S1A-001$A> <#> Yeah but

6

er 's the best goes top of the league <,> <{> <[>

you know

</[> <S1A-001$A> <#> <[> So </[> </{> it 's like

When to Build Custom Functions

Use custom functions when:

- Need character-based (not token-based) windows

- Want very specific extraction logic

- Learning how concordancing works

- quanteda doesn’t quite fit your needs

Use quanteda when:

- Standard concordancing suffices

- Want tested, optimized code

- Need integration with other quanteda features

- Working with complex token objects

Part 11: Reproducible Workflows

Professional research requires reproducible, well-documented workflows.

# At top of script # Title: Concordance Analysis of Character Names in Alice # Author: Your Name # Date: 2026-02-08 # Purpose: Extract and analyze character name patterns # Load packages library(quanteda) library(dplyr) # Set parameters CONTEXT_WINDOW <-5OUTPUT_DIR <- here::here("output", "concordances") # Load data text <-readLines(here::here("data", "processed", "alice_clean.txt")) # Extract concordances kwic_alice <- quanteda::kwic( tokens(text), pattern = quanteda::phrase("Alice"), window = CONTEXT_WINDOW ) |>as.data.frame() # Save results write_xlsx( kwic_alice, file.path(OUTPUT_DIR, paste0("alice_concordance_", Sys.Date(), ".xlsx")) ) # Session info (for reproducibility) sessionInfo()

Version Control with Git

For serious projects, use version control:

Benefits:

- Track all changes

- Revert to previous versions

- Collaborate safely

- Required by many journals

# Before concordancing summary(text) # Basic stats head(text, 50) # Look at the beginning str_count(text, "\\w+") # Word count

2. Start with Simple Patterns

Code

# Start simple kwic(tokens(text), "alice") # Then refine kwic(tokens(text), "alice", case_insensitive =TRUE) # Then get complex kwic(tokens(text), "\\b(alice|hatter).*", valuetype ="regex")

3. Validate Your Results

Code

# Check sample manually kwic_results |>sample_n(20) |>View() # Verify counts make sense nrow(kwic_results) # Does this seem right? # Check for edge cases kwic_results |>filter(str_length(keyword) >20) # Unexpected long matches?

4. Document Everything

Code

# What, why, when # Extracted: 2026-02-08 # Pattern: \\balice.* (all words starting with "alice") # Context: 5 tokens # Rationale: Investigating Alice's linguistic behavior

5. Save Intermediate Results

Code

# Save cleaned text saveRDS(text_clean, "data/processed/text_clean.rds") # Save raw concordances saveRDS(kwic_raw, "output/kwic_raw.rds") # Save filtered concordances write_xlsx(kwic_filtered, "output/kwic_filtered.xlsx")

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake 1: Forgetting Case Sensitivity

Code

# Problem: Misses "Alice" because searching for "alice" kwic(tokens(text), quanteda::phrase("alice")) # Solution: Use case_insensitive or search both kwic(tokens(text), quanteda::phrase("alice"), case_insensitive =TRUE)

# Exact word "alice"# Phrase quanteda::phrase("poor alice") # Word family "walk.*" with valuetype ="regex"# Starting with "\\bun.*" with valuetype ="regex"# Ending with ".*ing\\b" with valuetype ="regex"# Alternative "alice|hatter" with valuetype ="regex"

Bonus: